When Acceptable Becomes Absurd: The Issue of “Acceptable Accommodation and Food” for Migrant Workers Holding a Work Permit

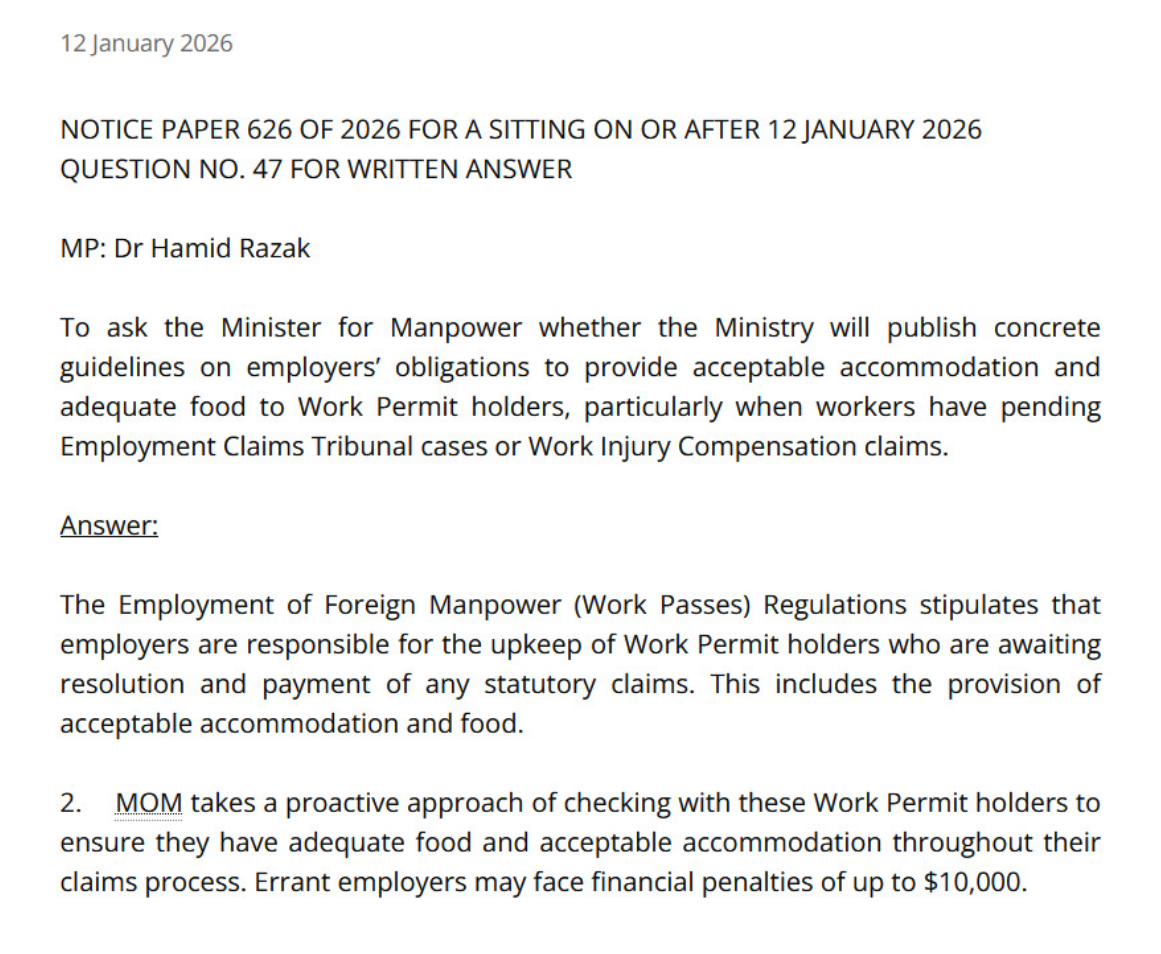

In January 2026, MP Hamid Razak filed a Parliamentary Question on the publication of concrete guidelines for accommodation and food for workers pursuing statutory claims against their employers. In its response, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) stated that employers are required to provide “acceptable” accommodation and food, and that MOM adopts a “proactive approach” by checking in with affected Work Permit holders to ensure they continue to receive adequate food and acceptable accommodation throughout the claims process.

Under the Employment of Foreign Manpower Regulations, employers are obliged to provide acceptable accommodation for workers undergoing statutory claims. No standard is prescribed for the provision of food.

HOME assists many workers with salary disputes, wrongful dismissal cases, and work injury claims. Unfortunately, a number of employers provide food and housing arrangements that are inadequate and unreasonable, exposing workers to indignity, anxiety, and significant distress. The following are some examples:

Worker 1: He had salary and wrongful dismissal claims against his employer. He had been paying for his own food and housing upkeep but had run out of funds to make rent. He faced eviction. Worker 1’s employer proposed for him to stay at the employer’s mother’s residence for the remaining duration of his claims, to which Worker 1 was not agreeable, given the breakdown of the employment relationship. The matter proceeded to mediation at MOM, during which the employer adamantly refused to provide alternative accommodation. Worker 1 was told that he was also not permitted to store his own cooked food in the refrigerator, purportedly due to the employer’s mother’s cancer. Only after intervention by HOME, during the mediation, was Worker 1 eventually placed in centralised housing arranged by MOM.

Worker 2: He had salary claims against his employer. He was asked to leave his MOM-arranged accommodation as his employer had arranged separate accommodation. However, when Worker 2 arrived at the location given to him in the morning (at Upper Thomson), he only found a construction site and no habitable accommodation. He returned to HOME’s office, where MOM contacted him and informed him that there was indeed a temporary dormitory at the location he had gone to. Worker 2 then returned to the location, but was denied entry by personnel there. It was only at 7pm that day, after spending the entire day shuttling between Upper Thomson, HOME’s office and back to Upper Thomson, that the employer picked him up to bring him to an accommodation in Sungei Tengah.

Worker 2's troubles were not over. He was made to travel twice daily from his accommodation in Sungei Tengah to his employer’s office in Ubi to collect an $8 daily food allowance, and was told that his accommodation would be revoked if he was late. His total travel time to collect his allowance to meet his basic food requirements exceeded 4 hours daily. He was also in the midst of looking for new employment and the unreasonable travel time impeded his ability to do so. After about two weeks, with HOME’s intervention, he was granted centralised housing again with MOM.

Worker 3: A food processing worker, she was given accommodation at a hostel in Chinatown by the employer, but was required to travel three times a day to Upper Changi at specific timings (8am-9am; 12pm-1pm; 6pm-7pm) to receive her meals. If she arrived late, she would have been recorded as a no-show. Her employer also did not secure long-term housing at the hostel, and was only willing to extend it every few days. This left her uncertain and anxious about her housing situation, since her case was scheduled to last a few months.

Worker 4: He was asked to change accommodation on a daily basis by his new employer, during and after the resolution of his salary claim.

Worker 5 was asked to stay in an apartment owned and occupied by her employer’s father. She was not given her own room, and had to stay in the living room with no privacy. She refused as she was afraid to stay alone in an apartment with a male occupant, much less someone who is related to her employer against whom she had made claims. Her friend housed her for a few days, and HOME is assisting her with temporary accommodation while she awaits a more permanent solution (see screenshot below).

If not for intervention by HOME and other NGOs, it is very likely that the workers would continue to have been subject to these demeaning conditions It is clear that the employers in these cases are effectively retaliating against workers who file claims by imposing demeaning arrangements that compromise the workers’ ability to meet their most basic needs.

The spirit of the regulations is that workers who are pursuing claims—an exercise of their legal rights—should have their basic needs met without fear or uncertainty. In this regard, HOME proposes the following recommendations:

Clear, published standards for food and accommodation ensuring workers’ safety and dignity.

Minimum housing and food allowances, where published standards cannot be met.

Early access to MOM’s centralised housing the moment it is clear that employers are uncooperative or fail to meet minimum standards.

Real consequences when employers fail their obligations.

Posted on 12 February 2026