A Fair Chance Denied: Burmese Workers Face Deportation Despite Securing Jobs

Six Burmese workers — Thiri, Ko, Aung, Saw, Mi, and Hemen — arrived in Singapore early in 2025, each carrying hopes and dreams of finding employment. Some were young, eager to build their careers and support their families back home, while others dreamed of providing a better future for their children. All six worked as construction workers.

Wage Theft

These workers told HOME they were promised jobs by a company in Singapore with pay of at least $30 a day. However, upon arrival, they found their daily wage was only $15.38. They also suspected they were not paid overtime and rest day pay as required by Singapore’s labour laws. They could not verify their claims without access to payslips or timecards, since they were not allowed to take photos or view these documents. Employers are required by law to issue itemised payslips to their employees.

When their IPAs were issued in Myanmar, they noticed the lower daily pay and raised the issue with their supervisor. He dismissed their concerns, saying it was common for IPA salaries to appear lower than actual pay and assured them they would receive around $30 daily. However, their actual salary was almost half of what they expected. This financial shortfall was especially difficult, as they needed to support their families back home while covering their own living expenses in Singapore.

Poor Living Conditions: Bedbug Infestations and Sleep Disruption

At the workers’ Sungei Kadut accommodation, bedbug infestations left them with unbearable itching and many sleepless nights. The problem was so severe that they had no choice but to sleep on the cold floor outside their rooms or in shared common areas. Their accommodation was also situated right beside the noisy construction site, where loud machinery and activity often continued well into the night. This constant disruption destroyed any chance of proper rest and recovery after a long and hard day at work.

Kickbacks: Paying for Their Own Jobs

The workers also informed HOME that they were pressured into handing over kickbacks to their company. Fearing job loss, they felt they had no choice but to comply. The amounts ranged from $1,800 to $2,800, all paid in cash, save for one worker, directly to their company. These payments were made under pressure, further deepening the workers’ financial hardship even before they began their jobs.

Outcome of Salary Mediation at TADM

When the workers filed salary claims at the Ministry of Manpower (MOM), they were told they could only claim based on the salary amount declared on their In-Principle Approval (IPA) letters — $15.38 per day, not the $30 they were verbally promised. Before the mediation, HOME had seen evidence that they should be paid at least $30. The salary mediation process concluded with the employer issuing a Consent Letter for Work Permit Transfer, allowing the workers to seek alternative employment. This offered them a brief sense of relief, as returning to Myanmar, where a civil war is ongoing, was unsafe. The consent letter from their employer was valid until 13 June 2025.

The Job Search Begins: Unsupported and Left to Struggle

Following the issuance of the consent letters, the workers began searching for new jobs. During this period, while they were provided with accommodation, no food was given. HOME assisted in supplying essential groceries like rice and eggs, as the employer failed to provide food upkeep. This abandonment not only violated Singapore’s labour laws but also denied these already vulnerable workers their most basic needs during a critical time.

Despite these challenges, progress was made. Thiri and Ko were issued their provisional approvals, new In-Principle Approvals (IPAs) on 4 June 2025, followed by Aung, Saw, and Mi on 9 June 2025.

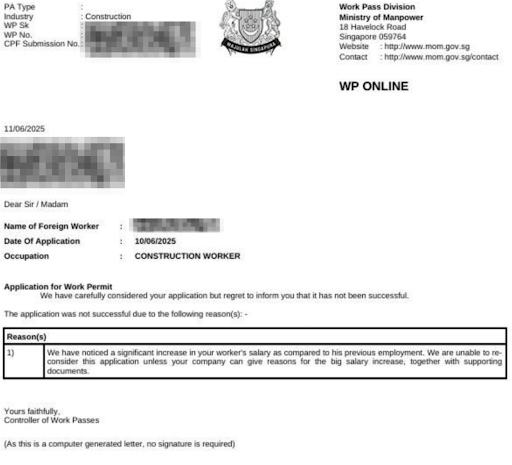

On 11 June 2025, Hemen’s IPA was rejected. According to the rejection advisory, the reason cited was a “significant increase in your worker’s salary as compared to his previous employment.” This is deeply unsettling, as workers usually have little control over the salaries offered to them (which can be very low, given that there is no minimum wage in Singapore). Despite having been misled and underpaid, Hemen felt hopeless after receiving the rejection of his IPA and decided to return back to Myanmar on 13th June 2025.

Possible Retaliation from Previous Employer

For Aung, Saw and Mi, their new employer had asked their former employer for medical records of these workers on 12 June 2025. On 12 June 2025, the former employer refused the new employer’s request for their medical records. As a result, the new employer had no choice but to arrange new medical tests, which took place on the morning of 13 June 2025.

The three workers also requested a short extension of the transfer window to complete the necessary administrative steps, but this was denied. The former employer cited 13 June 2025 as the final deadline and told them their Work Permits would be cancelled as they did not meet the deadline for transfer. When HOME reached out for clarification, the former employer claimed that the new employer no longer intended to proceed with the hiring, despite the issuance of IPAs and completion of new medical exams, both clear indications of intent to hire them.

On 14 June 2025, both the workers’ existing work permits and their newly issued IPAs were cancelled. Flights were booked for their repatriation on Monday, 16 June at 9 PM.

While HOME cannot verify the specific conversations between the former and prospective employers, we understand that consent from the former employer was initially required for the IPA applications to proceed. This raises serious concerns: Why was consent suddenly withdrawn after IPAs were approved? Why was a short extension refused, ultimately costing the workers their only chance to remain in Singapore?

Too Little Time, Too Much Control: Why Reform Is Urgent

The emotional toll on the workers has been severe. Even after overcoming salary inequities, they managed to secure new jobs and received IPA approvals, a process that initially required the consent of their former employer. Yet, in a sudden and devastating reversal, that same employer was able to block their transfer by simply refusing an extension of the transfer window. This sudden reversal shows how much control employers hold over the employment status of their workers.

The case of these six Burmese workers is not isolated. In recent months, HOME has seen a rising number of Burmese migrant workers seeking assistance, many reporting similar patterns of exploitation, sudden repatriation, and lack of recourse. These experiences highlight an urgent need to re-examine policies around work permit transfers.

Even after employers give their consent for transfer, they can still act in bad faith by withdrawing their consent. When workers are required to rely on the cooperation of employers who may have already mistreated them, the risk of retaliation or obstruction is high. Without stronger safeguards, workers are left vulnerable to losing their livelihoods through no fault of their own.

HOME urges the Ministry of Manpower to strengthen worker protections and ensure that once a worker has secured a legitimate job offer, that opportunity is not easily undone by employer obstruction. Migrant workers deserve a fair chance to work, and their livelihoods must be less dependent on their employers’ whims.